A Sinless Season

2023

Solo Exhibition

Everard Read Gallery, SA

2023

Solo Exhibition

Everard Read Gallery, SA

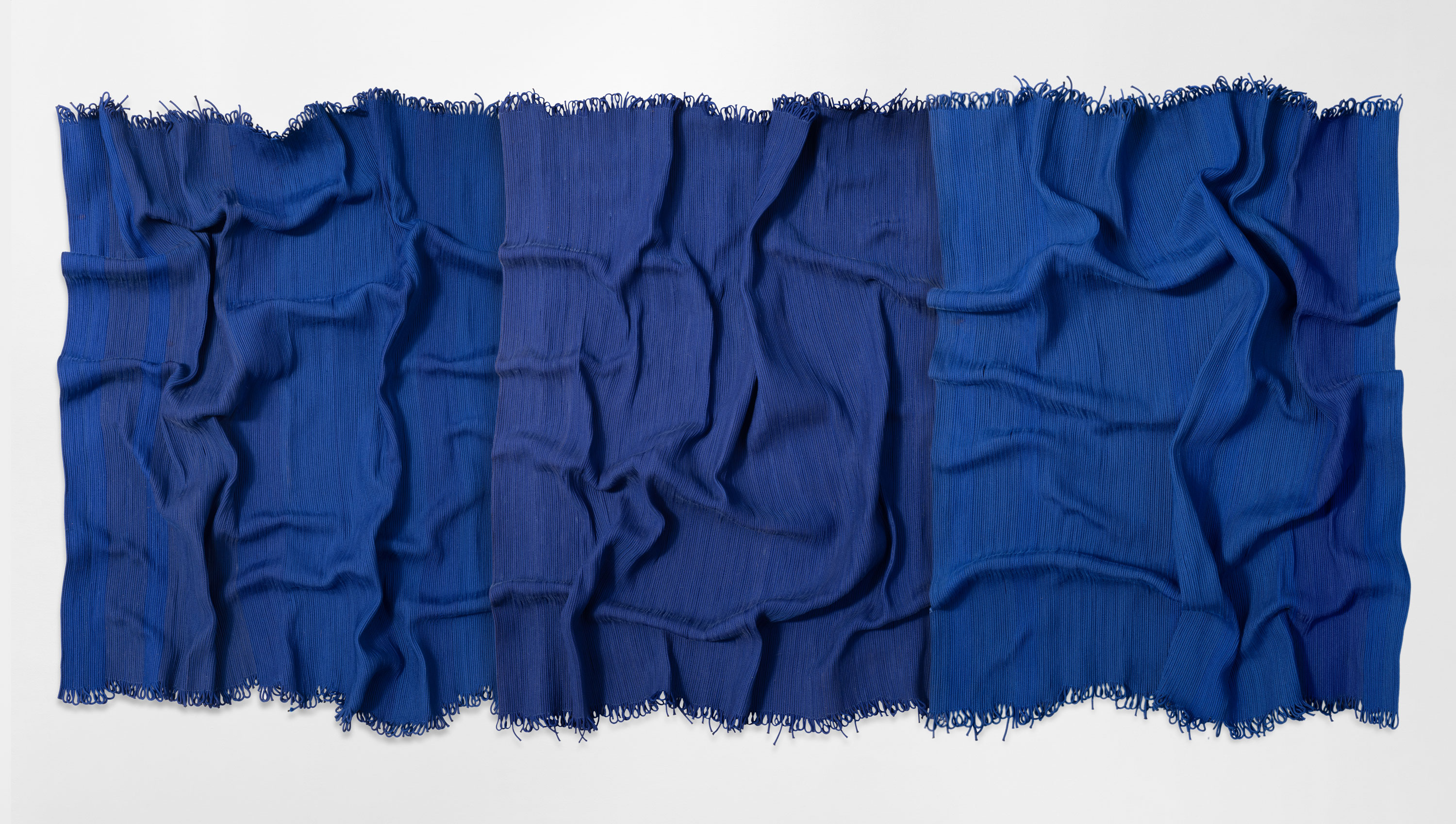

Anarchy of Desire

2023

Hand-dyed tissue paper

Dimensions variable

2023

Hand-dyed tissue paper

Dimensions variable

White flowers, death and flowering of pleasure

2023

Oil and ink on aluminium

109,5 x 83 cm

2023

Oil and ink on aluminium

109,5 x 83 cm

The Multitudinous Seas Incarnadine

2023

Sewn nautical rope

160 x 380 cm

2023

Sewn nautical rope

160 x 380 cm

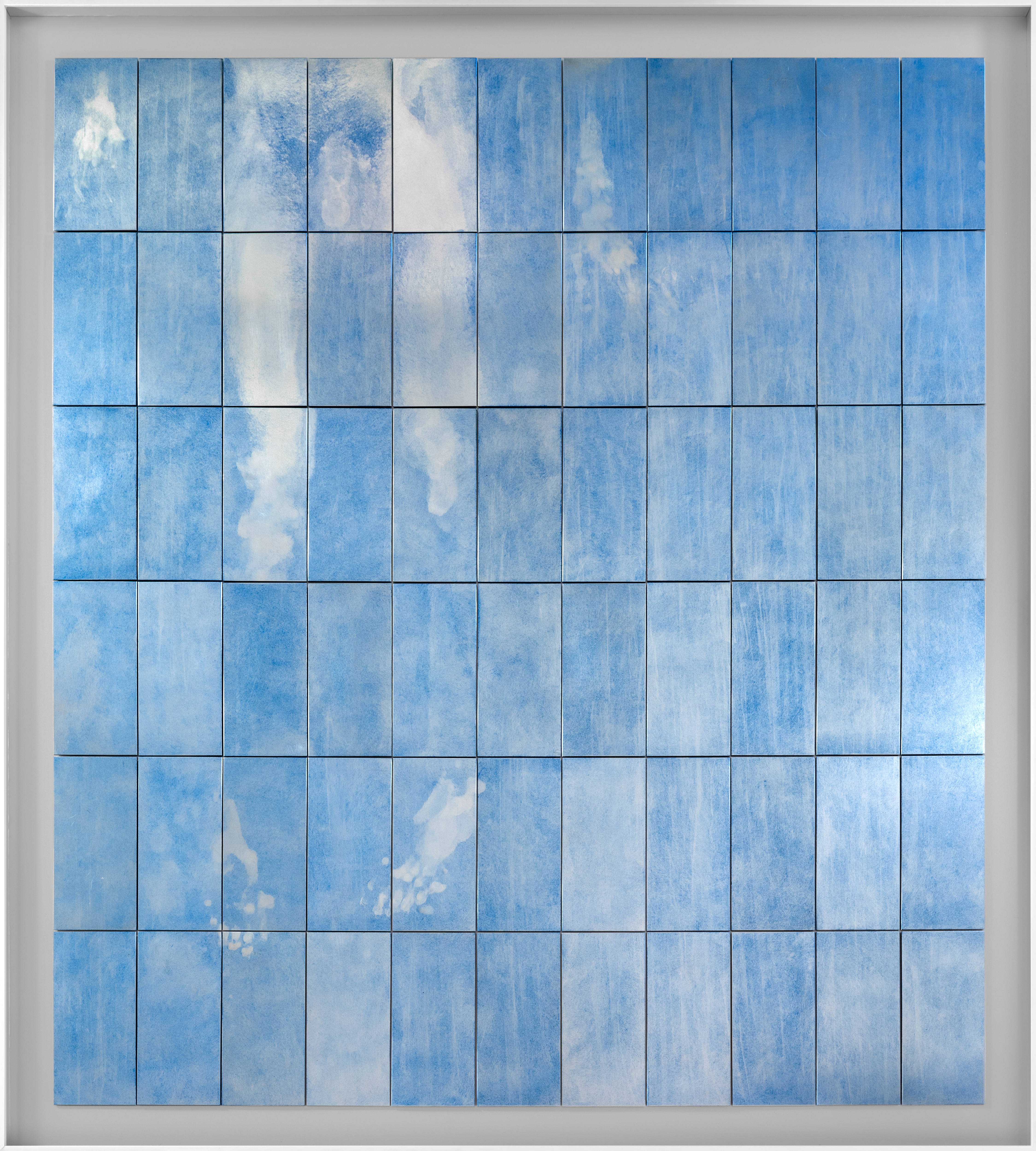

Like a blue frost, it caught them

2023

Oil on aluminium

167,5 x 151,5 cm

2023

Oil on aluminium

167,5 x 151,5 cm

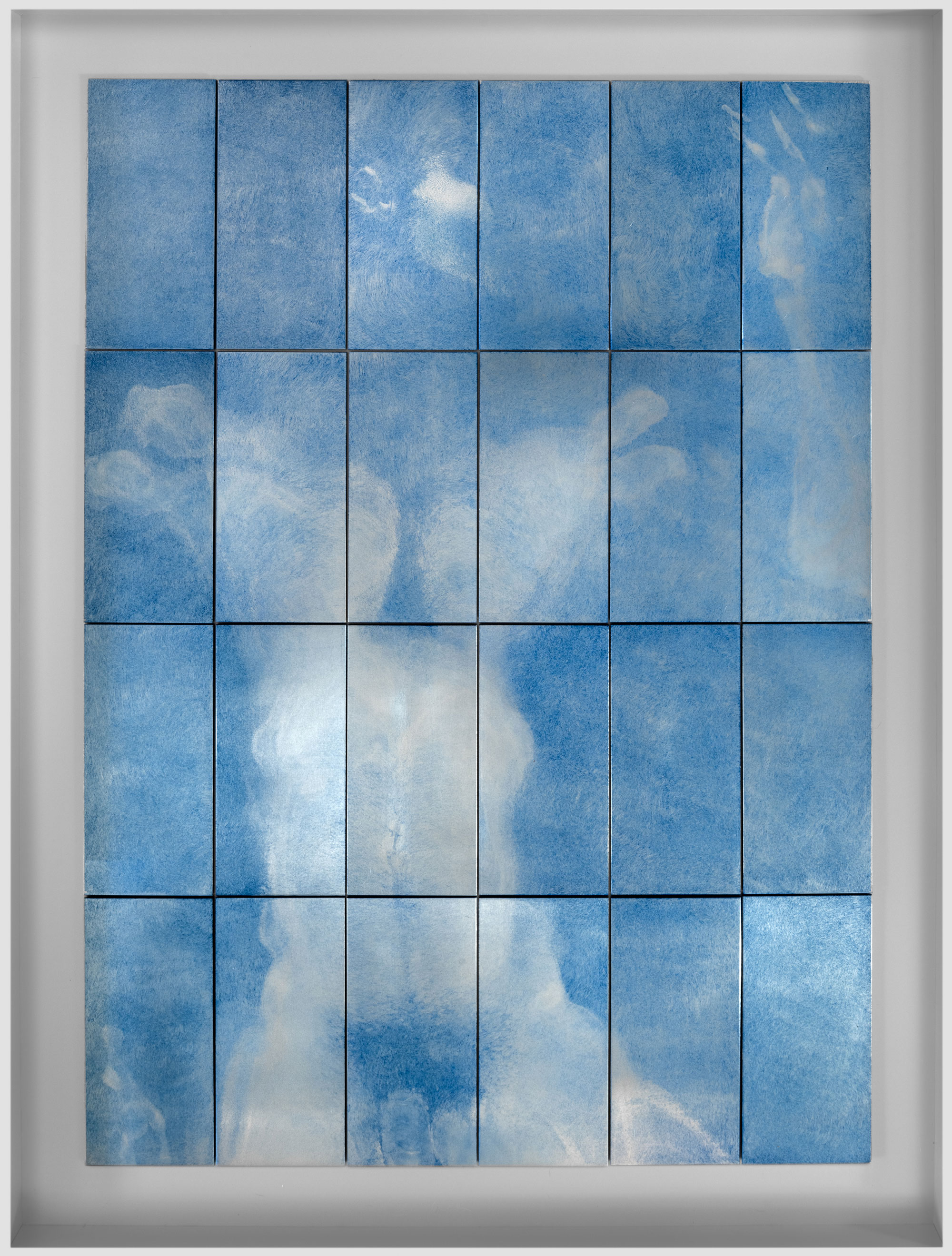

Horrifyimg as an angel I

2023

Oil on aluminium

109,5 x 83 cm

2023

Oil on aluminium

109,5 x 83 cm

Horrifyimg as an angel I

2023

Oil on aluminium

109,5 x 83 cm

2023

Oil on aluminium

109,5 x 83 cm

How did you cross the cobalt river? (The darkness comes in with the tide)

2023

Sewn nautical rope

120 x 110 cm

2023

Sewn nautical rope

120 x 110 cm

Beauty and the devil are the same thing

2023

Ink on paper

81 x 57 cm (per panel)

2023

Ink on paper

81 x 57 cm (per panel)

How did you cross the cobalt river? (In a deep embrace, salt lips touching)

2023

Sewn nautical rope

120 x 110 cm

2023

Sewn nautical rope

120 x 110 cm

A Sinless Season

2023

Solo Exhibition

Eveard Read Gallery, SA

2023

Solo Exhibition

Eveard Read Gallery, SA

Borrowed from the title of Damon Galgut’s debut novel, A Sinless Season marks a new thematic enquiry in Morné Visagie’s practice. In the artist’s words:

Much of my earlier work carries a longing for another. I was suspended in a state of melancholy and nostalgia; making work for an absent other, coveting something I could never have. An imaginary love, unrequited. The work was always turning on tragedy: the suffering of lovers condemned by another. With this latest body of work, there is a distinct sobriety. A novel decisiveness, a marked sense of independence. A figure appears, one that has been present yet unseen throughout my work. The figure of the artist – my own – alone and self-assured.

The exhibition, Visagie suggests, is composed of fragments that thread together, a series of tangential thoughts and gestures that, in turn, resonate with and resent one another. Together, these threads notate the artist’s preoccupations with themes of guilt and forgiveness. ‘Over the last few years,’ he writes, ‘I’ve come to realise that the blame I experienced in my youth was skewed and unfair. I was faultless in the cruel story of my being outed at the age of fifteen and the fall-out that followed. That I could only absolve myself of my assumed sin more than a decade later has made apparent the labour of transcending past traumas.’

Included in this exhibition are three compositions Visagie refers to as “bodyworks” – those figurative representations, however obscure, of the human form. These faint impressions of the artist’s body, present in Like a blue frost it caught them and the two works that share the title Horrifying as an angel, appear to float, suspended in blue. In previous works, Visagie has only intimated the presence of a figure in his architectural “drawings” of swimming pools, which appear as empty stages against which the imagination must cast characters. Here, instead, a moment’s clarity: a body, laid bare in its nudity, appears – insists its presence, however indistinct its likeness.

Where these three works reveal, Anarchy of Desire conceals. An installation of floor-to-ceiling pleated hand-dyed tissue paper, the piece is reminiscent of curtains. Drawn closed, and aglow in arctic blue, these fragile drapes are suggestive of another room from which the viewer is excluded, uninvited to witness the scene they hide. Their presence suggests a protected privacy. To this, Visagie asks, ‘What is the difference between privacy and secrecy? To which belongs the sacred and mysterious?’

A series of three blankets made from lengths of sewn nautical rope appear as abstracted seascapes. The initial impulse of these works, Visagie says, was to create a textile that might hold two bodies as a funerary shroud. He references shinjū, the Japanese phrase for a double suicide – two people dying in a gesture of tragic romance, their union denied by society, culture, religion or family. Much of Visagie’s earlier work has been framed around this idea of two lovers who cannot be together – who are sentenced to death. Now, however, such tragedy no longer seems inevitable to the artist. The blankets, made from nautical rope that will not perish, are reimagined as protective mantles. The lovers’ fate is not sealed but instead lent a symbolic safety.

Again, a repetition of threes: a triptych of infinite blues. Beauty and the devil are the same thing is composed of monochromatic prints that have been overprinted time and again until the paper became so saturated that it could not receive more ink. In form, it echoes both an altar and the mirrors of an old-fashioned vanity table. To the artist, these three fields of colour are an invitation to reflect on the self from three vantages. However, rather than seeing one’s own likeness as in a silvered surface, only a sea of blue; a reflection without refraction.

Ending on an ambiguous note, a lone photographic work, White flowers, death and flowering of pleasure, stands as a metonym of memory. In image, the work references Robert Mapplethorpe’s flower studies; in symbol, it suggests decay, death and funerary rites. ‘Arum lilies used to grow in abundance on Robben Island, where I grew up,’ Visagie recalls. ‘It was also the local school’s emblem. They remind me of childhood – of a time when I was never more free. In reality, however, the gardener who looked after these lilies was a prisoner and, at the end of every day, he would return to his cold hard cell.’ The lily remains an ambivalent presence among the motifs of his mind – at once fraught and fragile.

Together the accumulated works in A Sinless Season have about them a distinct coldness – there is no material warmth here, no wood nor brass nor copper. Only shades of blue and aluminium frames; a single black-and-white photograph. The exhibition is stark as a realisation is stark, immediate and unembellished. Yet in the cobalt light that spills across the space, the formal lyricism that shapes Visagie’s practice finds a compelling register, a sensuality without sentiment.

Much of my earlier work carries a longing for another. I was suspended in a state of melancholy and nostalgia; making work for an absent other, coveting something I could never have. An imaginary love, unrequited. The work was always turning on tragedy: the suffering of lovers condemned by another. With this latest body of work, there is a distinct sobriety. A novel decisiveness, a marked sense of independence. A figure appears, one that has been present yet unseen throughout my work. The figure of the artist – my own – alone and self-assured.

The exhibition, Visagie suggests, is composed of fragments that thread together, a series of tangential thoughts and gestures that, in turn, resonate with and resent one another. Together, these threads notate the artist’s preoccupations with themes of guilt and forgiveness. ‘Over the last few years,’ he writes, ‘I’ve come to realise that the blame I experienced in my youth was skewed and unfair. I was faultless in the cruel story of my being outed at the age of fifteen and the fall-out that followed. That I could only absolve myself of my assumed sin more than a decade later has made apparent the labour of transcending past traumas.’

Included in this exhibition are three compositions Visagie refers to as “bodyworks” – those figurative representations, however obscure, of the human form. These faint impressions of the artist’s body, present in Like a blue frost it caught them and the two works that share the title Horrifying as an angel, appear to float, suspended in blue. In previous works, Visagie has only intimated the presence of a figure in his architectural “drawings” of swimming pools, which appear as empty stages against which the imagination must cast characters. Here, instead, a moment’s clarity: a body, laid bare in its nudity, appears – insists its presence, however indistinct its likeness.

Where these three works reveal, Anarchy of Desire conceals. An installation of floor-to-ceiling pleated hand-dyed tissue paper, the piece is reminiscent of curtains. Drawn closed, and aglow in arctic blue, these fragile drapes are suggestive of another room from which the viewer is excluded, uninvited to witness the scene they hide. Their presence suggests a protected privacy. To this, Visagie asks, ‘What is the difference between privacy and secrecy? To which belongs the sacred and mysterious?’

A series of three blankets made from lengths of sewn nautical rope appear as abstracted seascapes. The initial impulse of these works, Visagie says, was to create a textile that might hold two bodies as a funerary shroud. He references shinjū, the Japanese phrase for a double suicide – two people dying in a gesture of tragic romance, their union denied by society, culture, religion or family. Much of Visagie’s earlier work has been framed around this idea of two lovers who cannot be together – who are sentenced to death. Now, however, such tragedy no longer seems inevitable to the artist. The blankets, made from nautical rope that will not perish, are reimagined as protective mantles. The lovers’ fate is not sealed but instead lent a symbolic safety.

Again, a repetition of threes: a triptych of infinite blues. Beauty and the devil are the same thing is composed of monochromatic prints that have been overprinted time and again until the paper became so saturated that it could not receive more ink. In form, it echoes both an altar and the mirrors of an old-fashioned vanity table. To the artist, these three fields of colour are an invitation to reflect on the self from three vantages. However, rather than seeing one’s own likeness as in a silvered surface, only a sea of blue; a reflection without refraction.

Ending on an ambiguous note, a lone photographic work, White flowers, death and flowering of pleasure, stands as a metonym of memory. In image, the work references Robert Mapplethorpe’s flower studies; in symbol, it suggests decay, death and funerary rites. ‘Arum lilies used to grow in abundance on Robben Island, where I grew up,’ Visagie recalls. ‘It was also the local school’s emblem. They remind me of childhood – of a time when I was never more free. In reality, however, the gardener who looked after these lilies was a prisoner and, at the end of every day, he would return to his cold hard cell.’ The lily remains an ambivalent presence among the motifs of his mind – at once fraught and fragile.

Together the accumulated works in A Sinless Season have about them a distinct coldness – there is no material warmth here, no wood nor brass nor copper. Only shades of blue and aluminium frames; a single black-and-white photograph. The exhibition is stark as a realisation is stark, immediate and unembellished. Yet in the cobalt light that spills across the space, the formal lyricism that shapes Visagie’s practice finds a compelling register, a sensuality without sentiment.

Edited by Lucienne Bestall