Tryst

2011

Graduate Exhibition

Michaelis Galleries, SA

2011

Graduate Exhibition

Michaelis Galleries, SA

Bridge

2011

Sea salt, porcelain, glass and wood.

Dimensions Variable

2011

Sea salt, porcelain, glass and wood.

Dimensions Variable

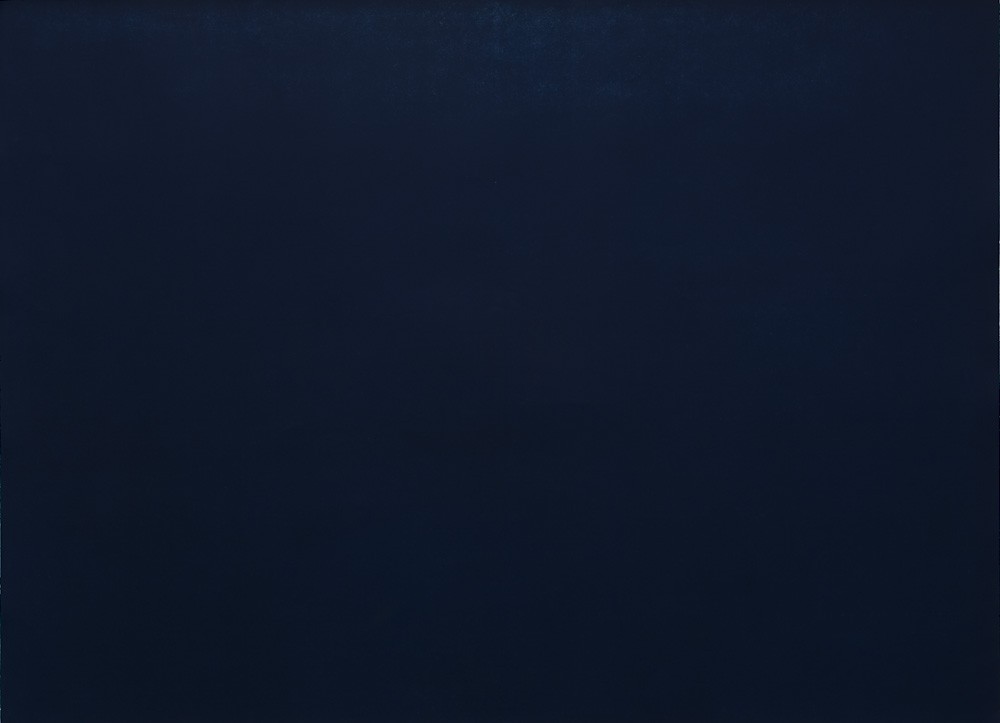

Will it forever travel into the void?

2011

Monotype on BFK Rives

120 x 160 cm

2011

Monotype on BFK Rives

120 x 160 cm

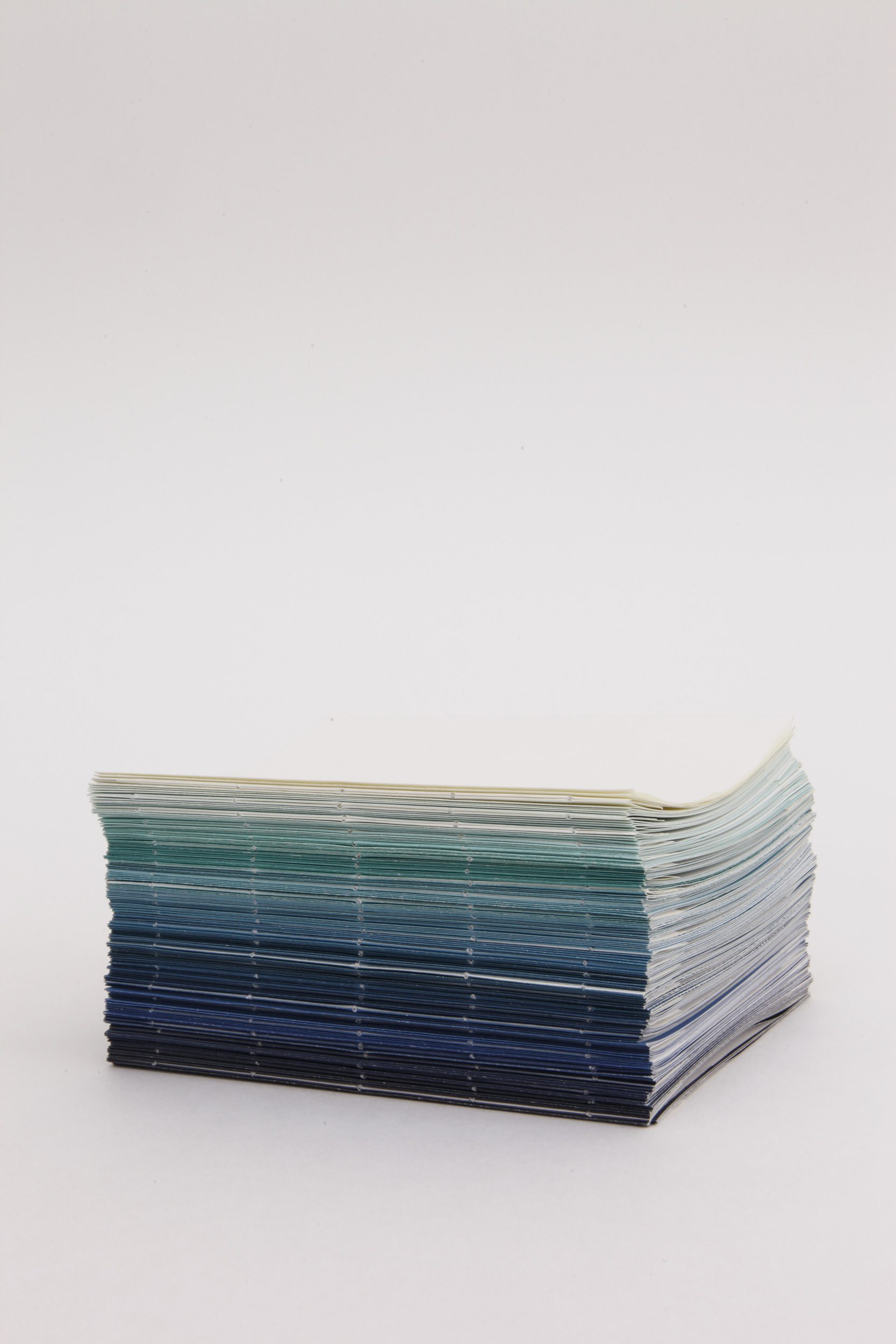

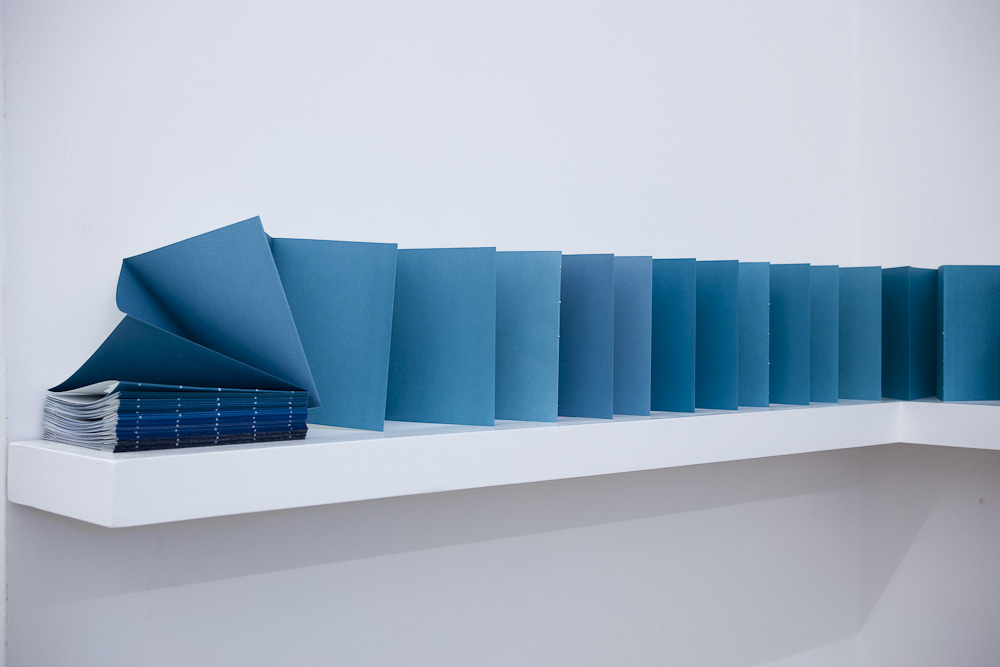

Travel Journal I

2011

Hand-stitched lithographs on Enigma 90gsm

Dimension Variable

2011

Hand-stitched lithographs on Enigma 90gsm

Dimension Variable

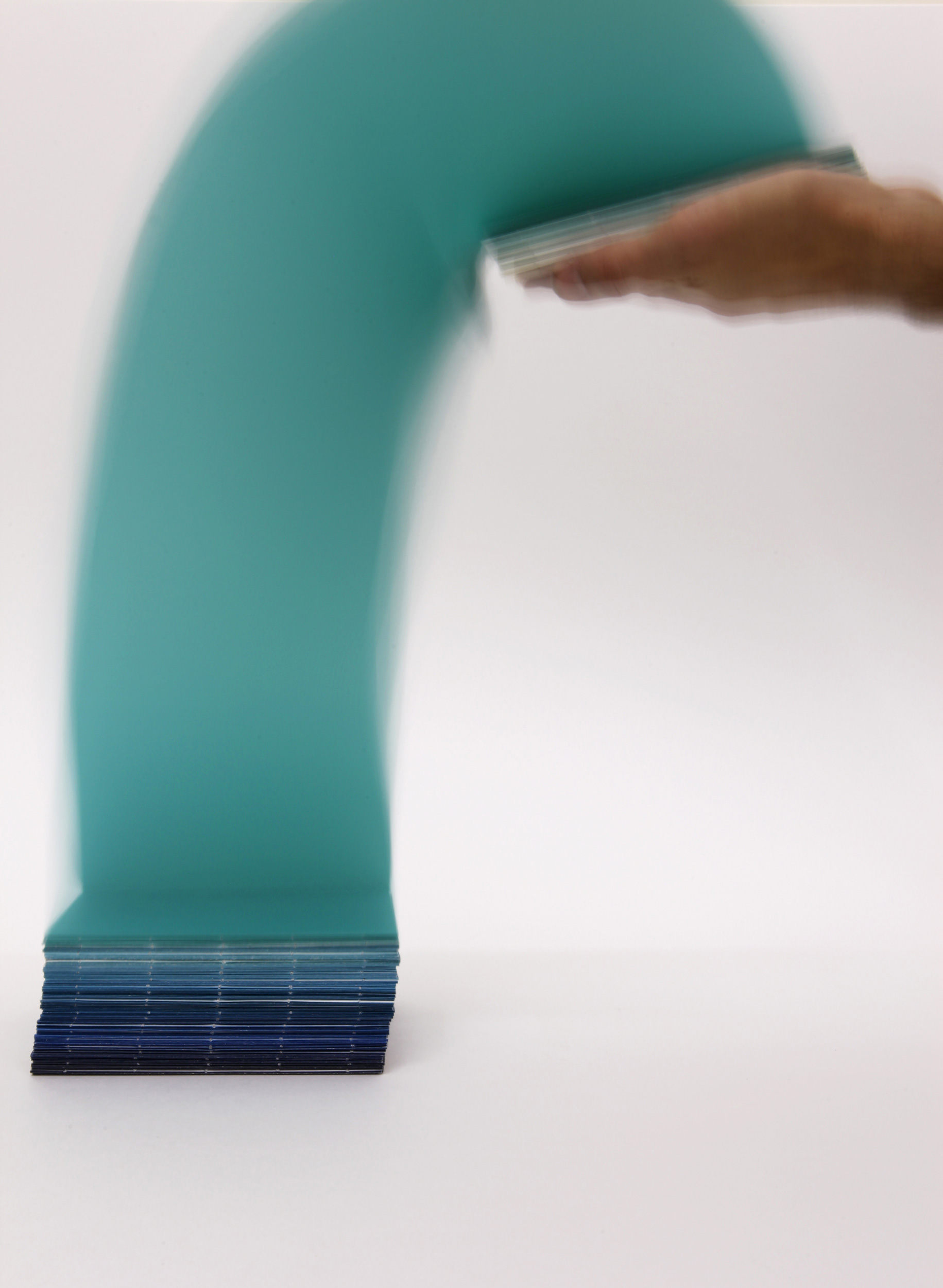

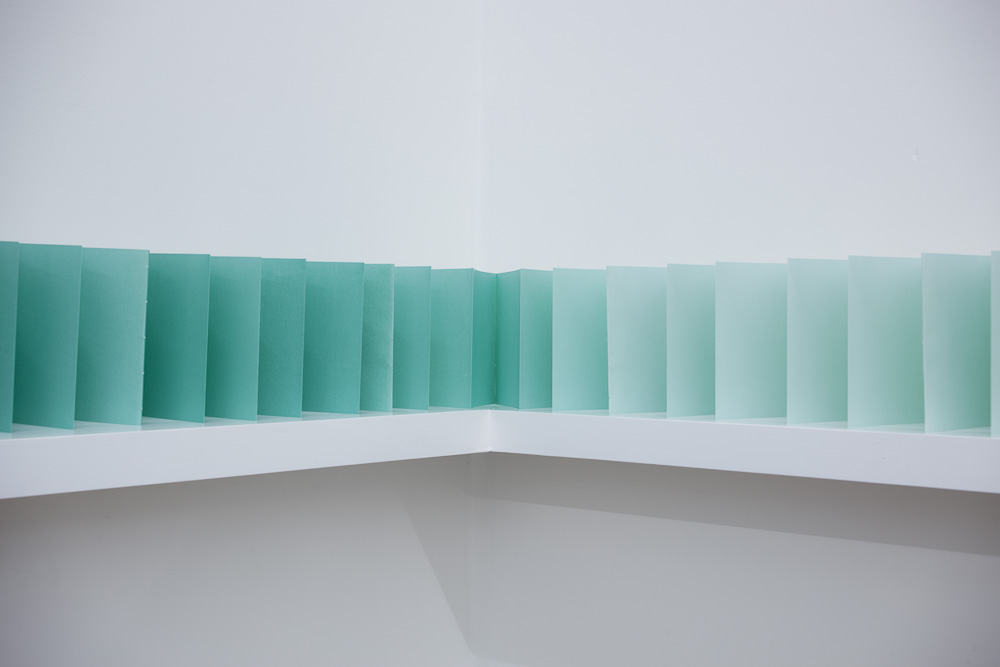

Travel Journal II

2011

Hand-stitched lithographic prints on Enigma 90gsm

Dimension Variable

2011

Hand-stitched lithographic prints on Enigma 90gsm

Dimension Variable

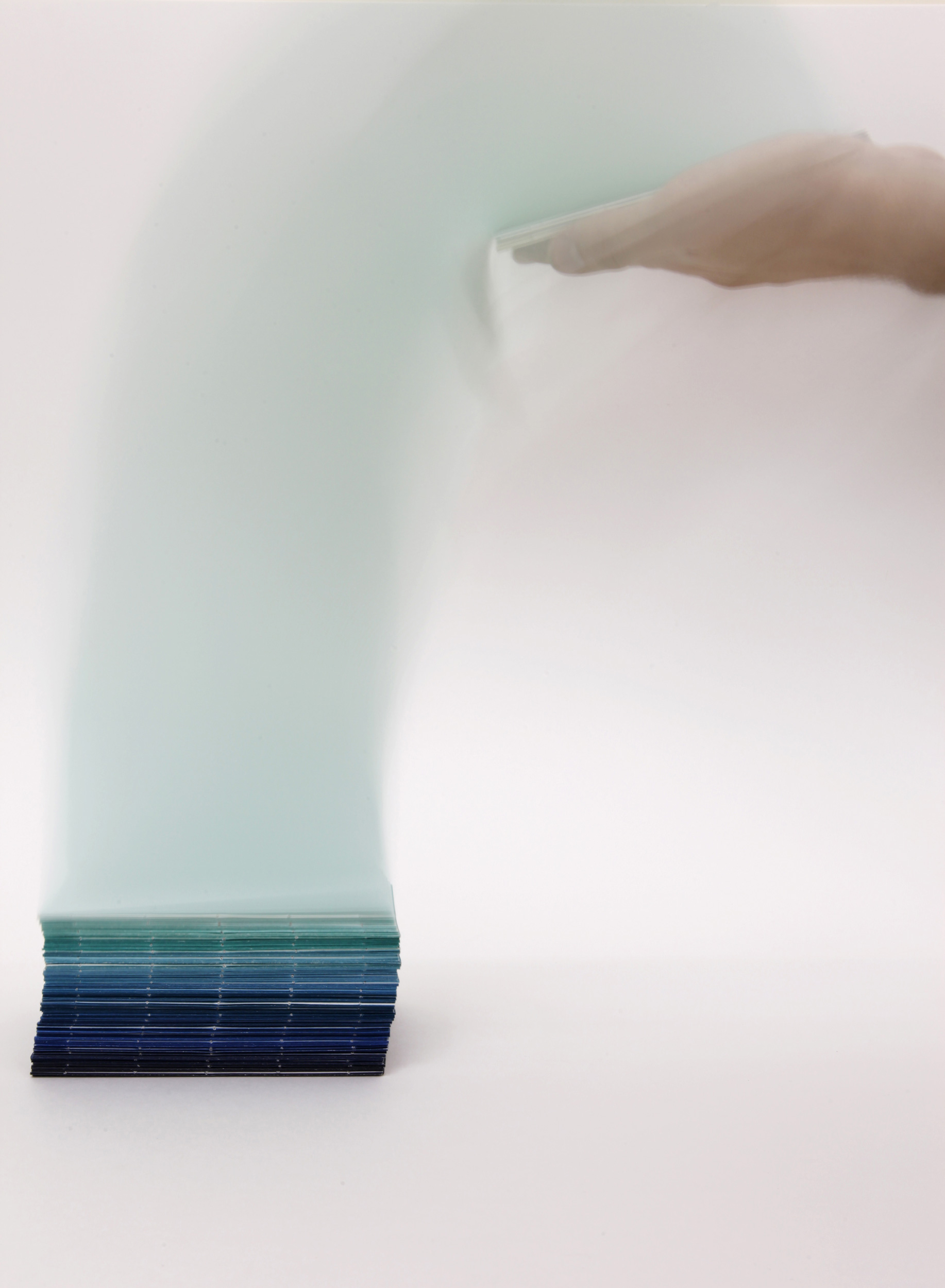

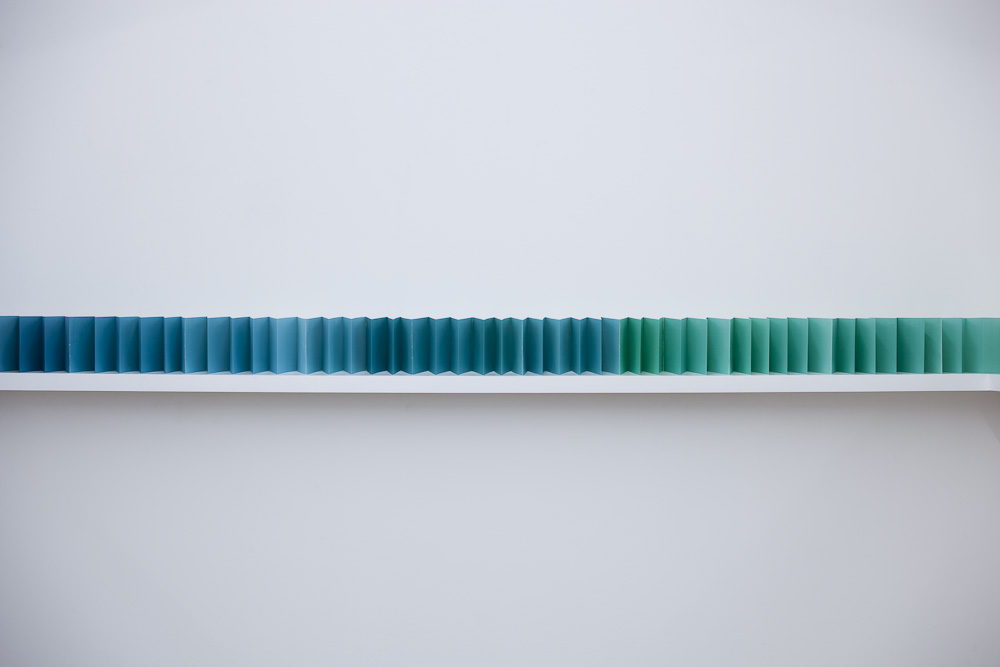

Travel Journal I & II (installation view)

2011

Hand-stitched lithographic prints on Enigma 90gsm

Dimension Variable

2011

Hand-stitched lithographic prints on Enigma 90gsm

Dimension Variable

As die ou lande weer blom

2011

Site-specifice performance and installation using dyed sea sand

Dimensions Varioable

2011

Site-specifice performance and installation using dyed sea sand

Dimensions Varioable

Perfect Lovers

2011

Screenprint on cotton and rope

60 cm Diameter (each)

2011

Screenprint on cotton and rope

60 cm Diameter (each)

Weather Guide

2012

Found Object (Japanese fishing buoy)

35 cm Diameter

2012

Found Object (Japanese fishing buoy)

35 cm Diameter

Felix Called it Loverboy

2011

Inkjet print on paper

40 x 60 cm

2011

Inkjet print on paper

40 x 60 cm

Landscape II

2011

Inkjet print on paper

80 x 150 cm

2011

Inkjet print on paper

80 x 150 cm

Notes

2011

Inkjet print on paper

25 x 50 cm

2011

Inkjet print on paper

25 x 50 cm

Tryst

2011

Graduate Exhibition

Michaelis Galleries, SA

2011

Graduate Exhibition

Michaelis Galleries, SA

tryst:

1: an agreement (as between lovers) to meet

2: an appointed meeting or meeting place

In the Eighteenth century sexual relations between people of the same gender were considered unnatural, abominable and an offence punishable by death. In the year 1713, Rijkhaart Jacobsz, a Dutch sailor sentenced to twenty-five years imprisonment, arrived on Robben Island. In 1715 Claas Blank, a Khoi-khoi, was sentenced to fifty years on the Island. In 1724, these men and other convicts went to Dassen Island to burn train oil. There, one night, in the small ‘bandieten hutje’ on the Island, they were secretly observed “committing an abhorrent sin” by a slave Augustijn Matthisz. Nothing was said about this for several years but in 1732 the same couple was caught in “the most compromis- ing of positions” in the ‘bandieten huysie’ of Robben Island by the two convicts Hermanus van Munster and Jacobus van der Walle. Munster and Der Walle went straight to tell Sergeant Scholz, the Postholder, who said that he could not do anything about such things and that the evidence of the convicts was worthless.

Some days later, however, when Rijkhaart Jacobsz walked past Sergeant Scholz who, on the pretext that Jacobsz had not raised his hat to him, beat him with a ‘daggetjie’. Where upon Jacobsz, in the pres- ence of others, shouted “Send mij maar op ek heb hom ‘n t_ _”. Scholz and his corporal, Wessels, were at a loss regarding how to react to this dreadful confession and they evidently hushed up the matter. Finally, in 1735, the truth was blurted out to Sergeant Willer when Jacobsz was beaten again because he had made improper suggestions to a slave. Willer beat Jacobsz until, in the presence of others, Jacobsz cried out, “Slaeniet, ek heb het gedoen, send my maar op!” Hermanus van Mun- ster stepped forward and informed Willer of the previously reported incidents.

In 1971, at the age of nine, my mother Juliana Visagie, together with her parents moved to the Island. Her father, Jacob Johann Folscher Le Roux, was a warder at the Department of Prisons (as it was then correctly called – they now refer to it as Correctional Services). They lived there for three years. In 1990, my father, Jacobus Gerrit Visagie, also employed by Correctional Services, was transferred to Robben Island. A few months after my birth, we moved to the Island which made my mother unhappy. The years she spent there as a child were lonely and isolated. In 1995, we had to move back to the main- land because the prison was announced inactive after the first demo- cratic elections in 1994 that changed the course of the future for South Africa. Today Robben Island is a National heritage site and the prison a museum.

Rijkhaart Jacobsz and Claas Blank have become central figures in my work. Rijkhaart, a Dutch sailor, represents the sea and Claas Blank, a Khoikhoi, represents land. These men met on Robben Island and here they had a secret love affair for a decade. The Island was a meeting place for the two. It is neither sea nor is it land. It is rock and sand within a mass body of water.

The body of work questions the construction of my own identity, the merging of land and sea and the third space, a tryst: the meeting place of two opposites. I investigate these questions through careful use of colour and representation. The works are devoid of all marks of self- expression and any pictorial diversity. Through the process of breaking information down into an abstract form, my aim is for the work to become less personal and through the process more public. My work derived from a personal experience and based on memory, cannot be conveyed to the viewer through mere pictorial imagery. Similar to Yves Klein’s blue monochromatic paintings, I am magnifying the idea of ambience in connection with notions of perception and reception.

Through a deeper reading of the site, its many histories and a look into my own heritage, in both Robben Island and Namaqualand, I have been able to determine key elements that links to demonstrate a relationship between the past and the present, whether or not it is my past and present or that of another. The Robben Island communal swimming pool is a point of intersection of several themes: memory and loss, through the representation of colour.