Multitudinous seas incarnadine

Solo presentation

The Norm (ICTAF, Cape Town, ZA)

Solo presentation

The Norm (ICTAF, Cape Town, ZA)

“Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood

Clean from my hand? No, this my hand will rather

The multitudinous seas incarnadine,

Making the green one red.”

If water could hold memory, what might that memory look like? In what form could it be seen, and how might it tell the many stories it has witnessed?

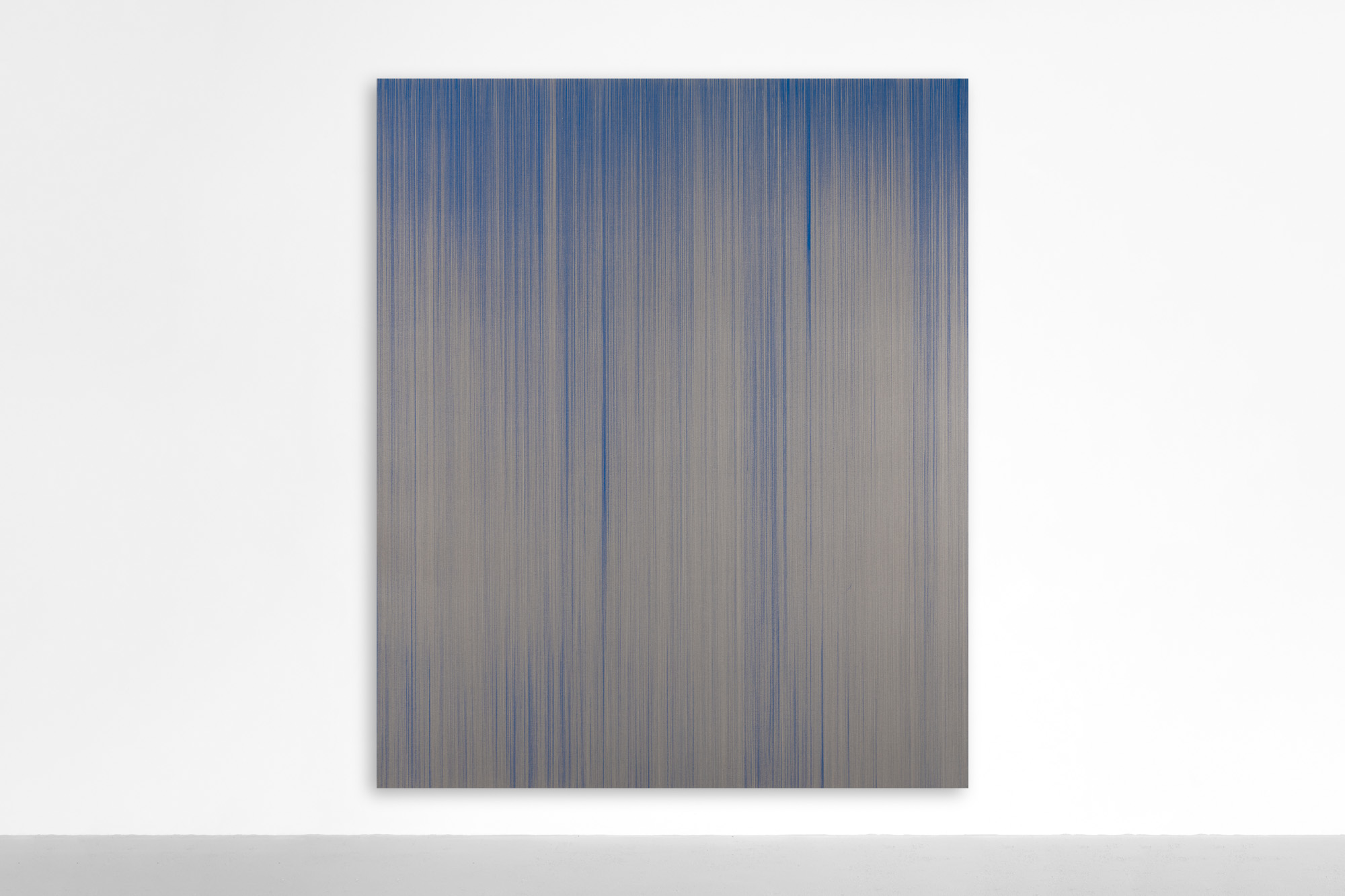

Take flight, in dawn’s first light

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

240 x 200 cm

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

240 x 200 cm

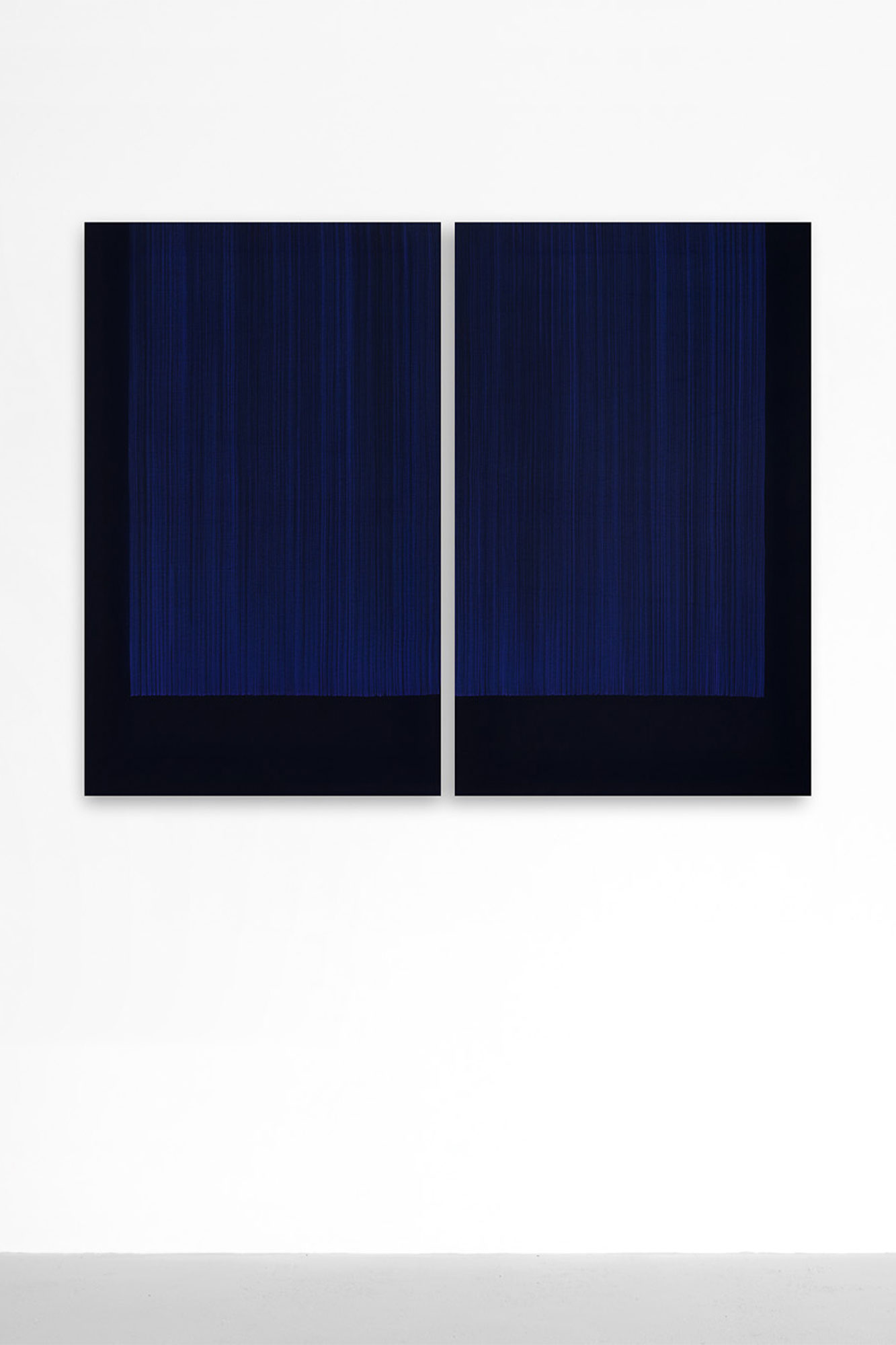

Terrestrial paradise (Cobalt)

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

200 x 240 cm (diptych)

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

200 x 240 cm (diptych)

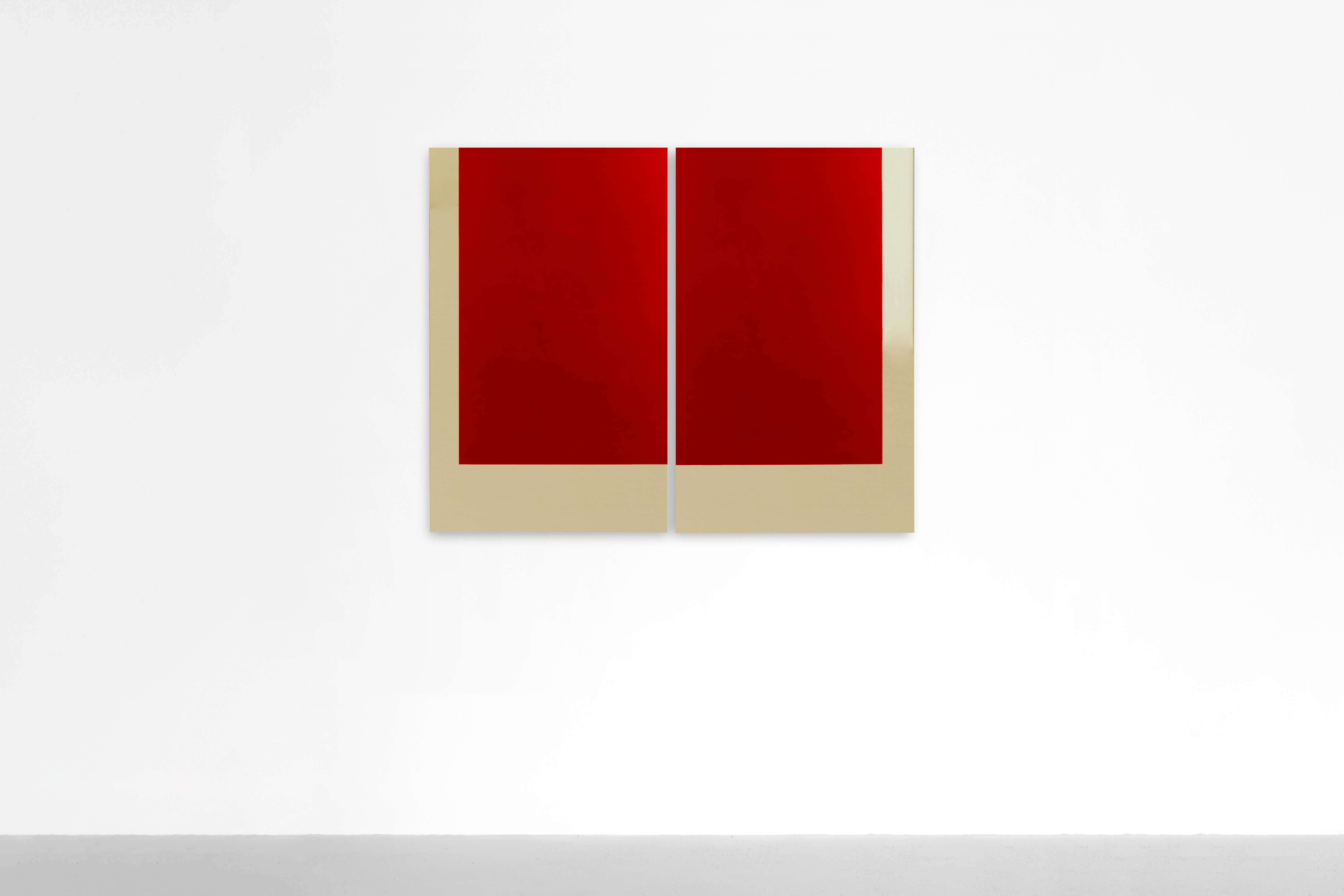

Multitudinous seas incarnadine

2026

Oil on brass

96 x 120 cm (diptych)

2026

Oil on brass

96 x 120 cm (diptych)

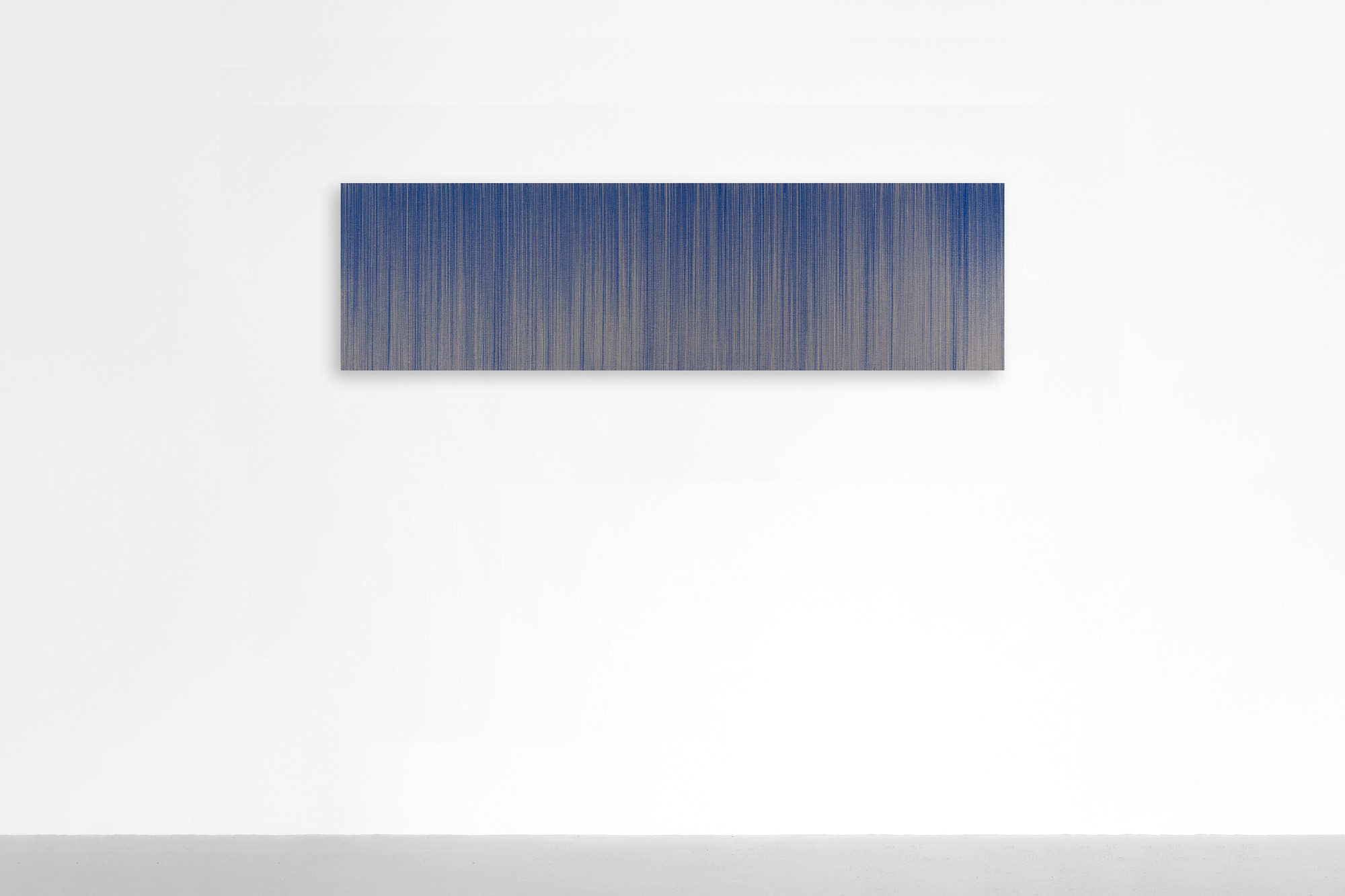

Blue light. A spectral light II

2026

Pencil on cotton

200 x 120 cm

2026

Pencil on cotton

200 x 120 cm

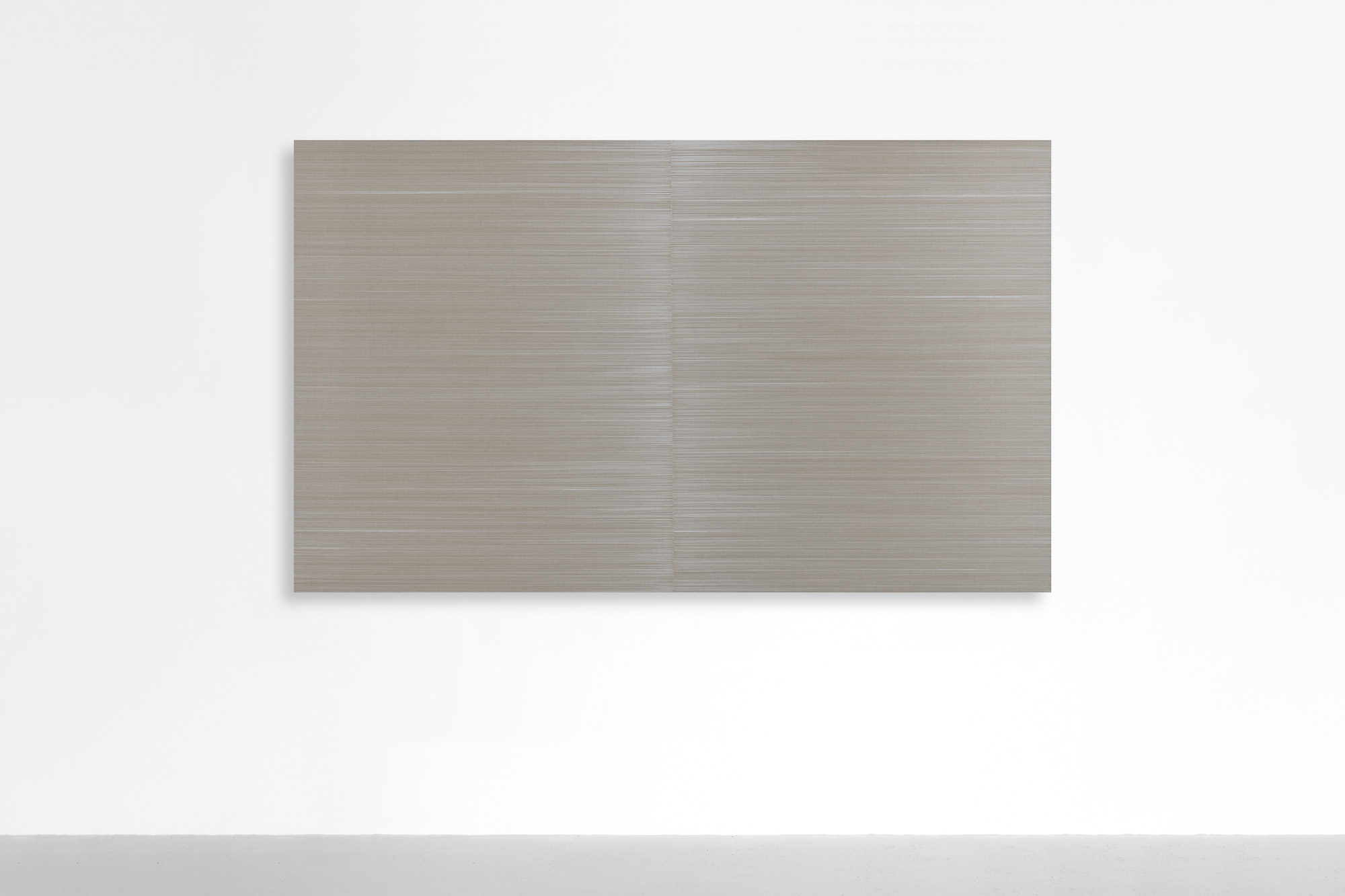

In the smoking chaos, our shoulder blades touched. I found you. (White)

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

120 x 200 cm

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

120 x 200 cm

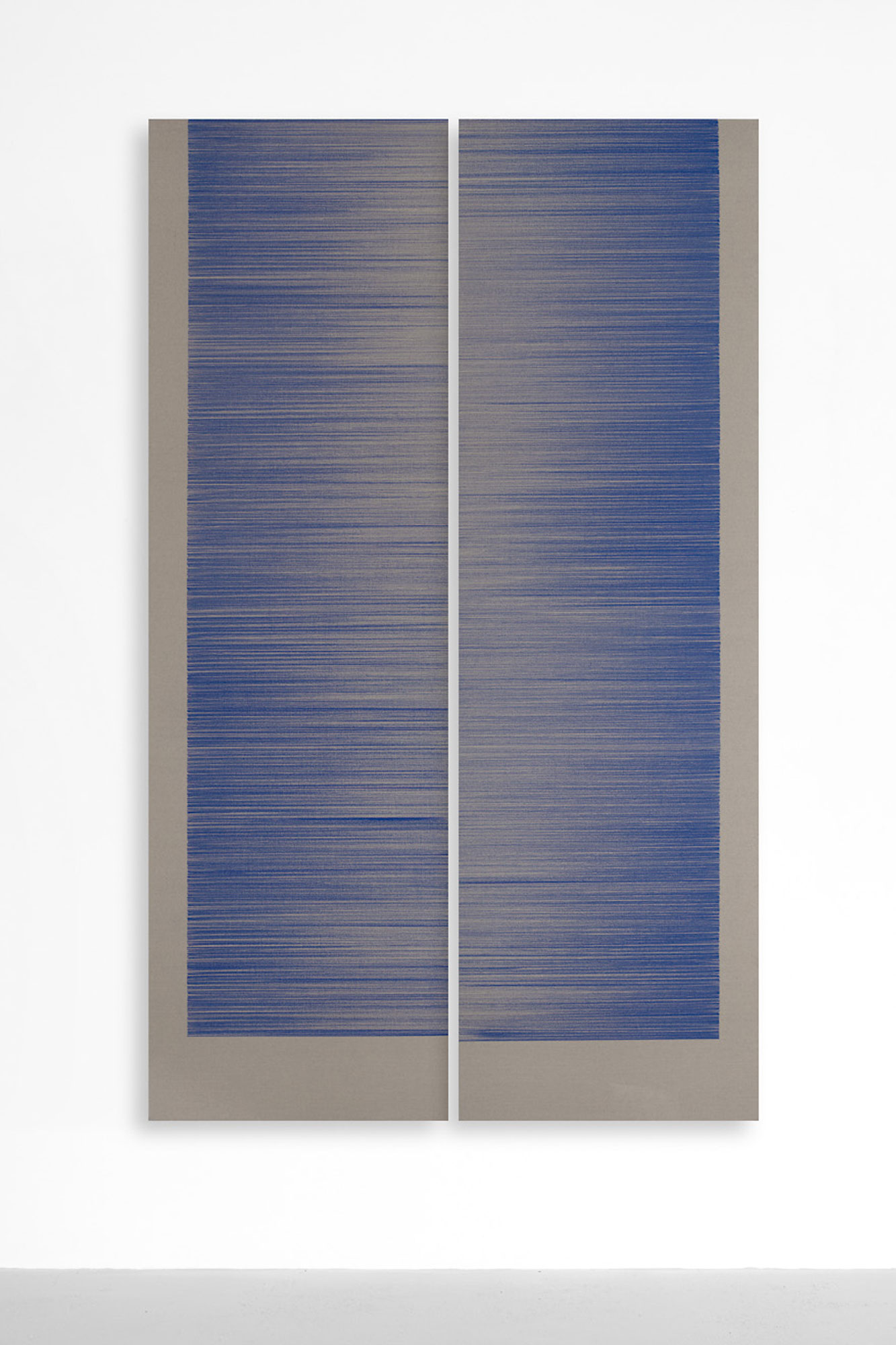

Terrestrial paradise (Ultramarine)

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

200 x 120 cm (diptych)

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

200 x 120 cm (diptych)

(Against my broken ribs your breast like a flower) II

2026

Pencil on stretched paper

200 x 120 cm (diptych)

2026

Pencil on stretched paper

200 x 120 cm (diptych)

(Against my broken ribs your breast like a flower) (Ultramarine)

2026

Pencil on cotton

96 x 120 cm (diptych)

2026

Pencil on cotton

96 x 120 cm (diptych)

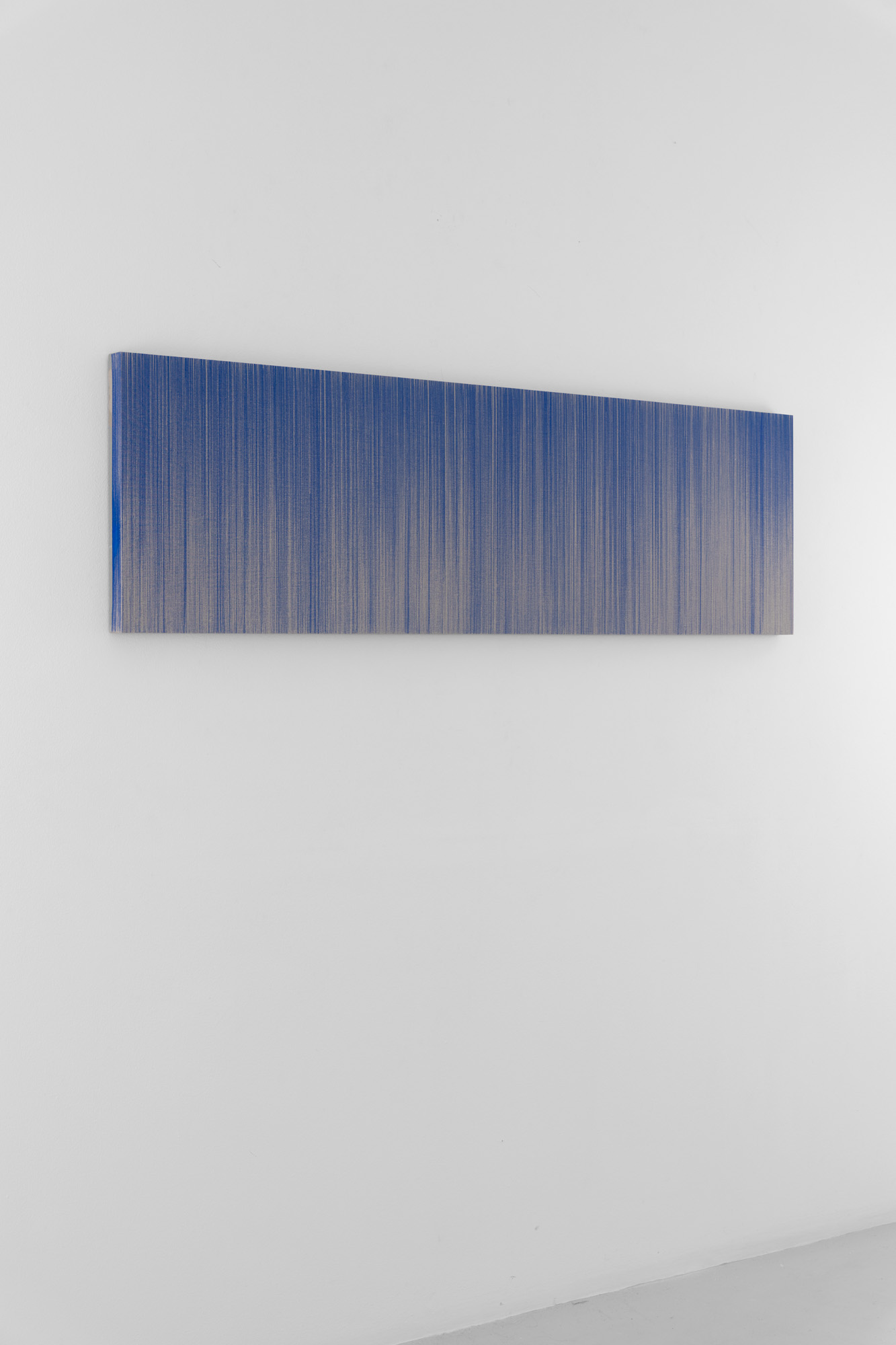

Take flight, in dawn’s first light (Fragment I)

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

52 x 183 cm

2026

Pencil on Italian cotton

52 x 183 cm

In the smoking chaos, our shoulder blades touched. I found you II

2026

Pencil on stretched paper

96 x 60 cm

2026

Pencil on stretched paper

96 x 60 cm

Blue light. A spectral light (Fragment I)

2026

Pencil on cotton

96 x 60 cm

2026

Pencil on cotton

96 x 60 cm

Halcyon days of youth III & IV

2026

Drypoint engraving on brass

40 x 25 cm / 64 x 40 cm

2026

Drypoint engraving on brass

40 x 25 cm / 64 x 40 cm

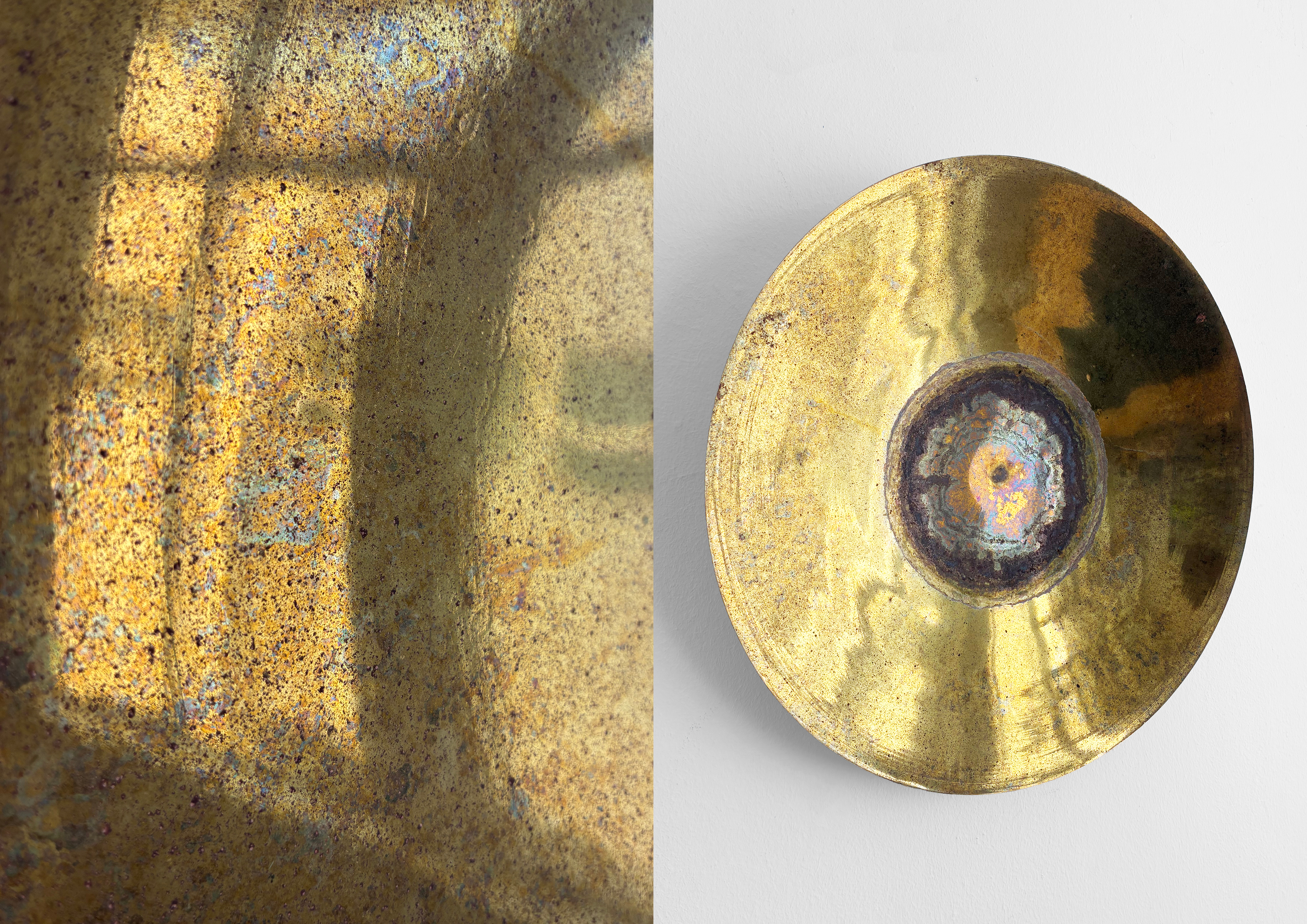

Fovntain (Gold I & II)

2026

Oxidised spun brass

40 x 40 x 6cm / 48 x 48 x 6 cm

2026

Oxidised spun brass

40 x 40 x 6cm / 48 x 48 x 6 cm

Fovntain (Crimson I & II)

2026

Oxidised spun brass

40 x 40 x 6cm / 48 x 48 x 6 cm

2026

Oxidised spun brass

40 x 40 x 6cm / 48 x 48 x 6 cm

Multitudinous seas incarnadine

Solo presentation

The Norm (ICTAF, Cape Town, ZA)

Solo presentation

The Norm (ICTAF, Cape Town, ZA)

The past year has seen Visagie’s preoccupations find a wider resonance in global narratives of migrancy. Where his earlier work proceeds from his biography outwards to consider water as a site and symbol in queer literature, his thematic considerations have since extended to include histories of ocean crossings. Such crossings have been, and continue to be, undertaken by those fleeing war, hardship, and persecution, those who dream of safe haven and hope for a better life.

For this presentation, Visagie is reminded of Two Brothers, a short story by South African author, Damon Galgut, which was written as an accompanying text for Fovntain, a solo exhibition by Visagie from 2018:

Fovntain series

The series of brass domes were first exhibited as a floor installation as part of Visagie’s solo exhibition Fovntain in 2018. Arranged in the gallery’s outdoor courtyard, the domes collected rainwater over the course of the exhibition. The water naturally oxidised the exposed brass, creating and leaving behind marks and patterns.

For Multitudinous seas incarnadine, Visagie returns to this work, selecting a number of the domes—some inked with red oil paint, others left in their original state. Drawing on Visagie’s printmaking methodology, akin to an etching plate where marks are made by hand, inked, and then printed onto paper, the domes were inked, with the rainwater marks holding the ink—the memory of water.

Now exhibited on a wall, the domes evoke the idea of porthole windows, looking out to sea and bearing witness to long journeys that “have been, and continue to be, undertaken by those fleeing war, hardship, and persecution—those who dream of safe haven and hope for a better life.”

For Visagie, the shift in colour from gold to red recalls a scene from Shakespeare’s Macbeth:

If water could hold memory, what might that memory look like? In what form could it be seen, and how might it tell the many stories it has witnessed?

For this presentation, Visagie is reminded of Two Brothers, a short story by South African author, Damon Galgut, which was written as an accompanying text for Fovntain, a solo exhibition by Visagie from 2018:

I.

To escape from their country, a man and his brother stow away on a ship. They hide below the deck, in a narrow space between two storage containers, the sound of massive engines working underneath them, and they are here for perhaps four days before they are discovered. Then they are dragged out into the light, which almost blinds them. The world is white and edgeless and they can hardly see the faces of the sailors who beat them, or the captain who sits in judgement on them, or the huge grey circle of sea that is now their fate. They are set adrift, clinging to the broken remains of a crate. They float through light, they float through dark. Their sight has come back to them, but there is nothing to see except for water, which takes on the infinite forms of absence, now pouring and flowing, now placid and still, now creasing into lines that rise and fall, rise and fall. They do not speak, or if they do, only a little, because words are no longer the point. Then the man’s brother drowns. He lets go of the crate and sinks beneath the water, his face twisted so that he seems to be smiling. (Or possibly he is smiling.) The clear lines of him hover for a moment, then fade away, as if he’s being erased. Light and dark, light and dark. How many times? Why does it matter? The man washes up on a stony beach, the edge of a continent he’s never stood upon before.

II.

Years later, he is working in a menial position in the home of a powerful government official. He sweeps floors, polishes shoes, carries things for people who don’t really see him. The man is no longer the man, not as he used to be. He has learned a new language, he has acquired a new name. He has made up a past which contains only elements of the truth. He hardly ever thinks about the real past, or only late at night, when he’s alone in his room. But on one particular day, the past rises up in him, against his will. He is sent to a courtyard to clean a fountain, which has become covered with verdigris. (Time undoes the world continually, only labour can restore it.) As he scrapes at the metal, something about the running water mesmerises the man, drawing him in and back, so that suddenly he is there again, in the instant where his old life ended. Vividly, intensely, he sees his brother, in the moment of his letting go. Except that this time he’s the one sinking under the water, the world fading gently overhead. And in this dream of drowning, the man enters a zone where he isn’t here and isn’t there, like a state of endless arrival. It’s beautiful in the place between places, where air has turned into water. You fall and fall endlessly, and it’s just like flying. Do you know what I mean?

Fovntain series

The series of brass domes were first exhibited as a floor installation as part of Visagie’s solo exhibition Fovntain in 2018. Arranged in the gallery’s outdoor courtyard, the domes collected rainwater over the course of the exhibition. The water naturally oxidised the exposed brass, creating and leaving behind marks and patterns.

For Multitudinous seas incarnadine, Visagie returns to this work, selecting a number of the domes—some inked with red oil paint, others left in their original state. Drawing on Visagie’s printmaking methodology, akin to an etching plate where marks are made by hand, inked, and then printed onto paper, the domes were inked, with the rainwater marks holding the ink—the memory of water.

Now exhibited on a wall, the domes evoke the idea of porthole windows, looking out to sea and bearing witness to long journeys that “have been, and continue to be, undertaken by those fleeing war, hardship, and persecution—those who dream of safe haven and hope for a better life.”

For Visagie, the shift in colour from gold to red recalls a scene from Shakespeare’s Macbeth:

“Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood

Clean from my hand? No, this my hand will rather

The multitudinous seas incarnadine,

Making the green one red.”

If water could hold memory, what might that memory look like? In what form could it be seen, and how might it tell the many stories it has witnessed?